What happens when a communist state abandons the communist experiment? In most cases, the state gets taken over by brutish strongmen, or, more happily, passes into the direction of its people through representative democracy. Only in East Asia, have communist leaders initiated profound economic reforms without losing political control.

Vietnam’s communism is like an old restored house. The house is old in the sense that the structure and style remain archaic, but inside, the occupants no longer build fires to heat the home. Vietnam still has the quaint relics of communism. Soldiers still loiter all around Hanoi, wearing oversized green uniforms and starchy caps ornamented with red stars. The government still uses billboard ads with happy proletariat scenes to publicize new initiatives. And a gang of old men still run the country through the Politburo, but these days they’re more likely to discuss foreign investment in IT, rather than production quotas.

Vietnamese citizens are no longer classified by their class backgrounds or judged by their revolutionary fervor. The government no longer tells them what to grow or what to make, nor does it seize their property at will. The Vietnamese are free to produce, to keep, to consume. But they aren’t free to decide the direction in which their country moves, nor do they select the leaders who move it.

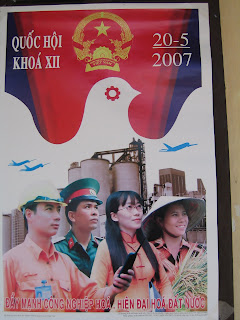

The Vietnamese do vote. All over the city, there are ads depicting a wholesome group of workers—an engineer joined with a student, a soldier and a farmer. The posters entreat the public to vote in a May election of the National Assembly a legislative body that meets in a relatively humble building to agree with the decisions of the Communist Party. 90% of the National Assembly are party members. The remaining 10% are labeled independents, because there are no other political parties in Vietnam. The National Assembly is in place to provide an electoral façade for the communist government, so that the Vietnamese can at least go through the motions of elective democracy. But they’re electing followers, not leaders.

National Assembly Building

The Vietnamese media is controlled but not stifled. Newspapers discuss politics openly and tempered criticism of government policies is permitted. The banned books list is still around but it’s smaller than it once was. It currently includes Paradise of the Blind, a modern novel about a family torn apart by cruel land reform policy. The government has long since acknowledged that the 1950s land-reform was a disaster, but would still prefer that people read about other things. I’m reading a bootlegged version that Desaix bought in an alley.

The media is not 100% free in Vietnam but overall the government does not use every means to control ideas. The internet is completely uncensored, in sharp contrast to neighboring China, where a friend could not access this blogsite. Millions of Vietnamese can now communicate freely online, publish their thoughts, and read what foreigners have to say about their country.

Government censorship is for the most part extremely half-hearted. Several people have told me that while the government discourages some topics, the Vietnamese can basically say whatever they want. Even democratization is widely discussed. But there’s one glaring exception to the government’s tolerance—suggesting that the Communist Party should relinquish its control over Vietnam is absolutely taboo. It is the only thing that Vietnamese actually go to jail for saying.

But remarkably, there are only a small handful of activists who’ve been locked up for promoting the overthrow of the party, and none of them equal the stature of Aung San Suu Kyi, the jailed Burmese freedom activist. Most of the locked up activists are fringe characters, considered loony by most Vietnamese.

Oddly, there’s not much of a serious opposition to the Communist Party. With a growing middle class that has fairly open access to news and ideas, it’s remarkable that there aren’t daily democracy demonstrations in Vietnam. There’s clearly something different about Vietnam’s communist government, something that distinguishes it from all the other un-democratic systems that struggle to survive amidst popular resistance.

The main reason for the security of the Communist Party is that almost everybody thinks it’s doing a good job running the country. Unlike most autocratic governments, the Communist Party remains in touch with the population. The Vietnamese want jobs and development, and the government is delivering spectacularly. Growth averages 9% annually and the private sector is adding thousands of jobs per day. Middle class expectations are rising, but so are incomes. Out of rural poverty, the Communist Party has brought an industrial boom to Vietnam.

Rahul Desai, an Indian-American financier involved in many Vietnamese business deals, told me that government officials are high-quality—eager to learn and adaptable to change. He described a government lacking charismatic figures like Ho Chi Minh, but run by competent technocrats who work feverishly to deliver growth and development to Vietnam.

The Vietnamese are very pleased by their country’s long-overdue economic growth. After so many decades of poverty, there’s a sense of euphoria which mutes potential democratic opposition. The Communist Party recognizes that it must keep the population content to maintain its monopoly on power. Madame Minh, a senior party official, told our class that the government’s most pressing concern is to ensure that the countryside benefits from the growth. If the cities grow richer, but the countryside stays poor, there will be millions of dissatisfied peasants and slum dwellers in years to come. That would spell trouble for any government.

When pressed, Madame Minh admitted that the process of democratization is moving slowly. But she did contend that it’s moving, which is true. Desaix told us that ten years ago, the National Assembly wasn’t “any more useful than a rock”. Now, the number of independents is growing and the assembly occasionally challenges some of the Party’s policies.

But at this rate, it would still take a hundred years for Vietnam to evolve into a true democracy. Luckily, there are signs that the Party leadership eventually intends to speed up the process. Desaix related that during his time reopening the American embassy in Hanoi, Party officials often asked him about foreign democratic systems. They were especially curious about Mexico’s PRI, and Taiwan’s Kuomintang, two revolutionary parties that stayed in power well after their countries democratized. A new class of Communist Party leaders, now trained in Europe and the United States instead of the Soviet Union, may one day decide to allow real opposition, with the expectation that the Communist Party will remain dominant.

For the individuals who run the Communist Party, there’s a lot at stake in ensuring that the Party stays in power. As Vietnam grows wealthier, there is more and more money to be made by governing it. Corruption in Vietnam is widespread, but top Party officials do not typically steal directly from the treasury, in the manner of African dictators or Latin American strongmen. Instead, they’re involved in networks of patronage and protection which are less criminal, but equally lucrative. Large foreign investors still work through the government, so top officials have opportunities to enter the choicest investments on favorable terms. Officials and their families can expedite permits, and circumvent laws. Until a few months ago, there was an infamous, debauched Hanoi nightclub which regularly blasted music until the early morning. Even though bars are supposed to close down at midnight, the owner was never fined and made enough money to cruise the streets in Vietnam’s only Hummer. It turns out that the owner’s father is a high Party official.

The Communist Party is no longer an ideological movement, but its leaders have a personal interest in its continued management of Vietnam. They may move toward democracy, but it will be at their own speed and their own terms.

But at some point, the people may take things into their own hands. The Communist Party is secure today because society is pleased with the tremendous wealth creation, but tomorrow there may be dissatisfaction. Most Vietnamese seem to think that their country will soon catch up to Japan or Singapore. But there are many, many obstacles to overcome before that happens, and if the government fails to deliver further growth, it will loose vital support. Additionally, if urban-rural income gap widens, millions of disaffected peasants could agitate for change.

The long term dominance of the Communist Party depends on its future economic success, which is far from certain. But for now, Vietnamese people will remain happy, docile, and un-free.

No comments:

Post a Comment